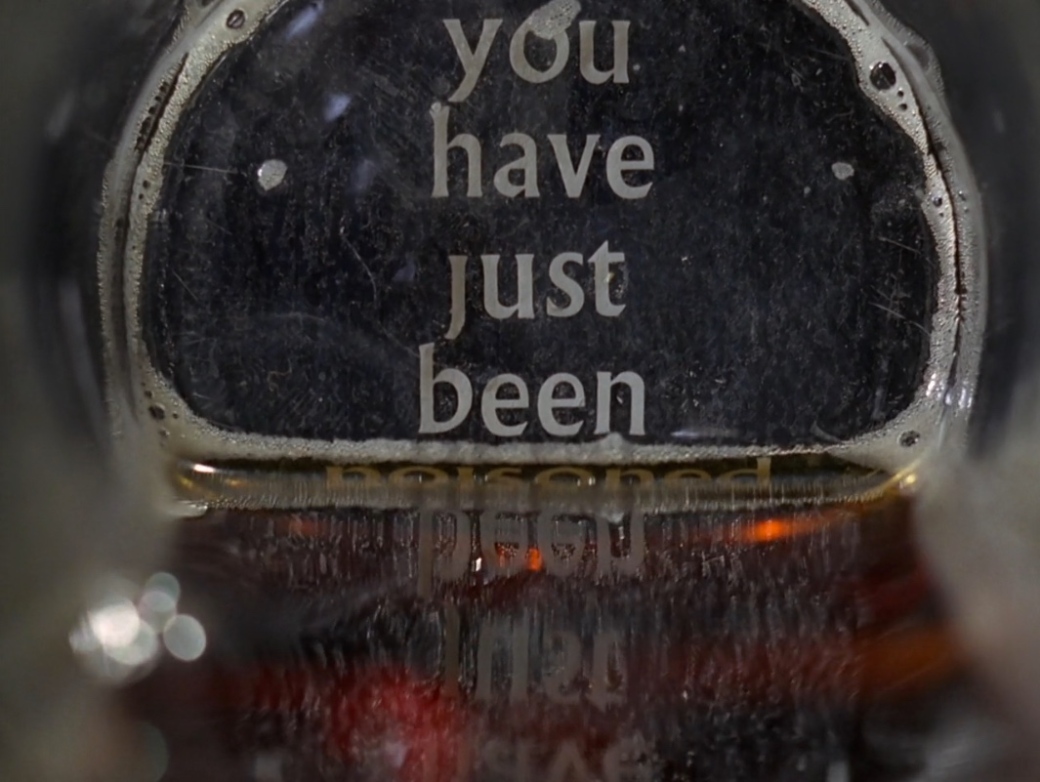

In “The Toxin Puzzle”, Gregory Kavka presents the following thought experiment. An eccentric but completely trustworthy billionaire offers to give you one million dollars on the condition that at midnight tonight, you intend to drink a toxin (which he will provide) tomorrow afternoon. The toxin will make you violently ill for a short time, but it is not life-threatening, nor will it leave any lasting harm. Moreover, you will receive the million dollar payment regardless of whether or not you drink the toxin. You just need to intend to drink it. Of course, because it’s a thought experiment, the billionaire has a perfectly reliable mind-reading machine he can use to determine whether or not you’ve held up your end of the bargain, so you really do have to have that intention at midnight tonight in order to collect the payout.

At first you think you’ll just intend to drink it at midnight, but as soon as you’ve collected those sweet simoleons you’ll flush that toxin down the toilet and skip all the unpleasantness. The problem is that this plan is incompatible with intending at midnight to drink the toxin the next day. In order to collect, you have to genuinely intend to do something that you know you will have no reason to do when the time comes around. That makes it rational to intend to do something that it would be completely irrational for you to do. And Kavka thinks this is something we’re incapable of doing. He concludes:

One cannot intend whatever one wants to intend any more than one can believe whatever one wants to believe. As our beliefs are constrained by our evidence, so our intentions are constrained by our reasons for action.

I love this paper and I find the conclusion pretty compelling. I wonder if there’s a less far-fetched but equally vivid parallel case, though. It seems to me that Kavka’s toxin puzzle is routinely played out by mercenaries and private sector bodyguards. A mercenary or bodyguard ought to be able to command a higher fee by intending to die for his or her employer if necessary for the sake or the employer’s interests, so the bodyguard or mercenary has good reason to intend to die for his or her employer if that does turn out to be necessary. At the same time, it is clear in advance that there would be no good reason to actually take a bullet for his or her employer if the necessity arose.

Kavka’s hypothetical scenario makes for a beautiful armchair argument that the manifest irrationality of the intended action (in his case, drinking the toxin) precludes the formation of the rationally justified intention (the intention to drink the toxin). But if the case of bodyguards and mercenaries is close enough to the hypothetical case of the toxin puzzle (and I think it is), this seems like an issue that could also be studied empirically. I’d be curious to know if it has been.