A man stands alone at the plate. This is the time for what? For individual achievement. There he stands alone. But in the field, what? Part of a team. Teamwork…. Looks, throws, catches, hustles – part of one big team. Bats himself the live-long day, Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and so on. If his team don’t field… what is he? You follow me? No one! Sunny day, the stands are full of fans. What does he have to say? “I’m goin’ out there for myself. But… I get nowhere unless the team wins.”

A man stands alone at the plate. This is the time for what? For individual achievement. There he stands alone. But in the field, what? Part of a team. Teamwork…. Looks, throws, catches, hustles – part of one big team. Bats himself the live-long day, Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and so on. If his team don’t field… what is he? You follow me? No one! Sunny day, the stands are full of fans. What does he have to say? “I’m goin’ out there for myself. But… I get nowhere unless the team wins.”

A couple of weeks ago, the Toronto Sun ran an op-ed proclaiming the end of the debate of on income inequality, and although I normally wouldn’t bother with the Sun, this column was written by Sean Speer, a Munk senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Speer’s credentials and affiliations lend him more credibility than most Sun columnists, so I think it’s worth taking the time to go over some grave defects of this piece.

Speer bases his column on a recent literature review by Yale psychologists Christina Starmans, Mark Sheskin and Paul Bloom, which found that people do not find economic inequality intrinsically objectionable. Inequality is objectionable only when it is unfair, and inequality is not always unfair. As the authors acknowledge, there is a large body of research supporting the claim that people do object to inequality as such. The problem with previous studies, they argue, is that test subjects lack the kind of information about each other that could justify unequal shares — information such as relative need, desert, merit, or bargaining power. So these studies only show a weak presumption in favour of equality; departures from strict equality will be objectionable if they are arbitrary, but not all such departures are arbitrary. When subjects have access to information that could justify unequal shares, they are happy to accept certain inequalities as fair. So it seems that fairness, not equality, is what people fundamentally care about.

From this finding, Speer draws the conclusion that people do not find economic inequality objectionable, and the further conclusion that economic inequality is not objectionable. Redistributive policies are misguided; instead, governments should seek only to equalize opportunities. All parties can share the goal of promoting social mobility, and each one has different ideas for how to promote it. Economic inequality, on the other hand, is truly polarizing; the left and the right do not even agree that there is a problem that needs solving. So the focus on economic inequality locks us into an unproductive partisan standoff, while shifting the focus to social mobility allows for a more promising policy-oriented debate around shared priorities.

Speer makes a number of surprising leaps here, but I’d like to focus on just two. The first is the claim that existing material inequalities are acceptable as long as they are fair, and they will be fair just as long as there is equal opportunity. In fact, Starmans, Sheskin and Bloom acknowledge grounds beyond fairness for objecting to existing inequalities, such as concern about poverty. Even if the current level of inequality is fair, concern about poverty gives us a good reason to make people’s economic status more equal. As long as this more equal distribution would also be fair, we have decisive reasons to prefer greater equality.

So, would the more equal distribution be fair? Speer provides only a single criterion of fairness: equality of opportunity. It follows that any distribution consistent with equality of opportunity — including a strictly equal distribution of income and wealth — is potentially a fair distribution. That means selecting equal opportunity as the sole criterion of fairness doesn’t close the debate on income inequality at all; if anything, it blows the topic wide open.

But is equal opportunity really all there is to fairness? This is hard to believe. A coin toss would give a prosecutor and an accused criminal equal opportunity to achieve their preferred outcome, but a defendant whose fate was determined by a coin toss could hardly be said to have received a fair trial. Fairness demands the impartial assessment of relevant reasons for choosing some outcome. A coin flip is, in this context, impartial but arbitrary rather than fair because it fails to take any of the relevant reasons into account. A fair procedure for determining guilt and punishment must be shaped by the need to establish a decisive connection between the strength of the available evidence and the conviction of the accused. Likewise, any number of economic arrangements that would satisfy equality of opportunity may yet be criticized on grounds of fairness because they fail to take relevant reasons into account, or give undue weight to some (nevertheless relevant) reasons over others. In fact, this is one of the key findings of Starmans, Sheskin and Bloom’s paper. If equal opportunity were all that fairness required, strictly equal distributions could not have been rejected on grounds of fairness.

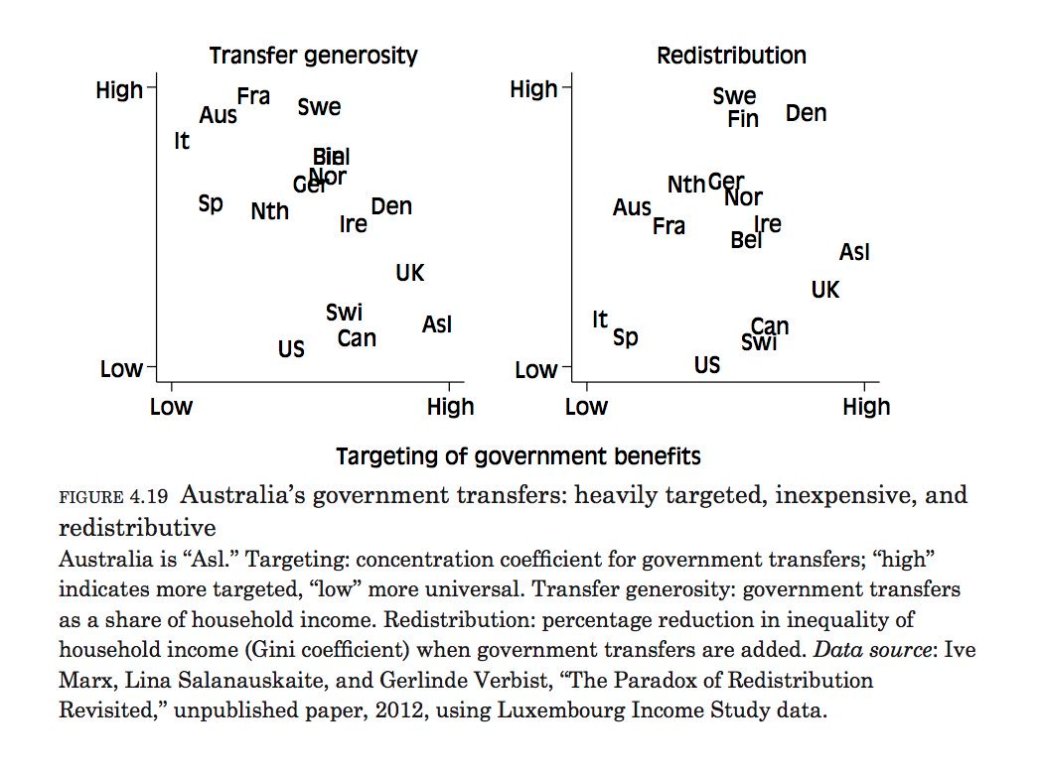

Under the assumption that fairness requires only equal opportunity, Speer concludes that fairness does not require redistribution. However, he soon contradicts himself, citing the relatively egalitarian Nordic states as models for Canada to follow in pursuit of greater social mobility. Moreover, one of his favoured social mobility-enhancing policies turns out to be redistribution via the child benefit system. Equality of opportunity depends on more equality of outcome and thus more redistribution after all. But as we’ve seen, there is more to fairness than equal opportunity. So does fairness require even more redistribution than equal opportunity? If so, why?

Recall that the authors find a common thread between studies that find support for a presumption of equality in that “recipients are indistinguishable with regard to considerations such as need and merit.” In many cases where we must decide on the distribution of some good, recipients are distinguishable on these bases. It’s not so hard to pick which employees should get a raise or which runners should get a medal, for example. But economic justice concerns the distribution of goods on the scale of an entire society. And at this level, recipients are indistinguishable from one another. Even if a free society could come to an agreement on criteria of need and merit in this context, it could not hope to reliably track each person’s need and merit and remunerate them accordingly — at least not without abolishing the market economy and instituting a totalitarian surveillance state. So fairness does justify a presumption of strict economic equality after all.

However, this presumption only establishes an egalitarian baseline. Departures from the egalitarian baseline cannot be justified on grounds of individual desert, but they can be justified on other grounds. Market economies are more productive, efficient and innovative than the alternatives, and these virtues depend on the signalling and incentive effects of an inequality-generating price system. As long as everyone is made better off by departure from equality, everyone has reason to endorse such departures. Fair inequalities in the overall distribution of income and wealth in society, then, will be those that conform to something like John Rawls’s difference principle, which requires that economic inequalities maximally benefit the least-advantaged group in society. Unless the least-advantaged group in our society is already as well off as it can be — which strikes me as extremely implausible — a good deal more redistribution is certainly needed to bring about a fair economy.

Speer’s frustration with the “tired” debate on income inequality is understandable, given how little progress on the issue there has been in recent years. But the findings he cites tend to support rather than undermine the issue’s importance by showing that concern about inequality is derivative of a more fundamental concern for fairness. This explains the importance of equality; it does not show that equality is unimportant. Because a focus on equal opportunity alone fails to fully respond to the value of fairness, and cannot in any case be achieved without a greater degree of economic equality, Speer’s call to abandon redistribution and pursue social mobility is deeply misguided.

A man stands alone at the plate. This is the time for what? For individual achievement. There he stands alone. But in the field, what? Part of a team. Teamwork…. Looks, throws, catches, hustles – part of one big team. Bats himself the live-long day, Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and so on. If his team don’t field… what is he? You follow me? No one! Sunny day, the stands are full of fans. What does he have to say? “I’m goin’ out there for myself. But… I get nowhere unless the team wins.”

A man stands alone at the plate. This is the time for what? For individual achievement. There he stands alone. But in the field, what? Part of a team. Teamwork…. Looks, throws, catches, hustles – part of one big team. Bats himself the live-long day, Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and so on. If his team don’t field… what is he? You follow me? No one! Sunny day, the stands are full of fans. What does he have to say? “I’m goin’ out there for myself. But… I get nowhere unless the team wins.”